Corry Shores

Who’s the Real Paul Masson? Personal Non-Identity in Deleuze’s Orson Welles (2021)

Elad Magomedov

Russo-Ukrainian War and Propaganda (2022)

Belief in Aliens as a Naturalistic Superstition (2022)

The Phantasm of American Greatness (2022)

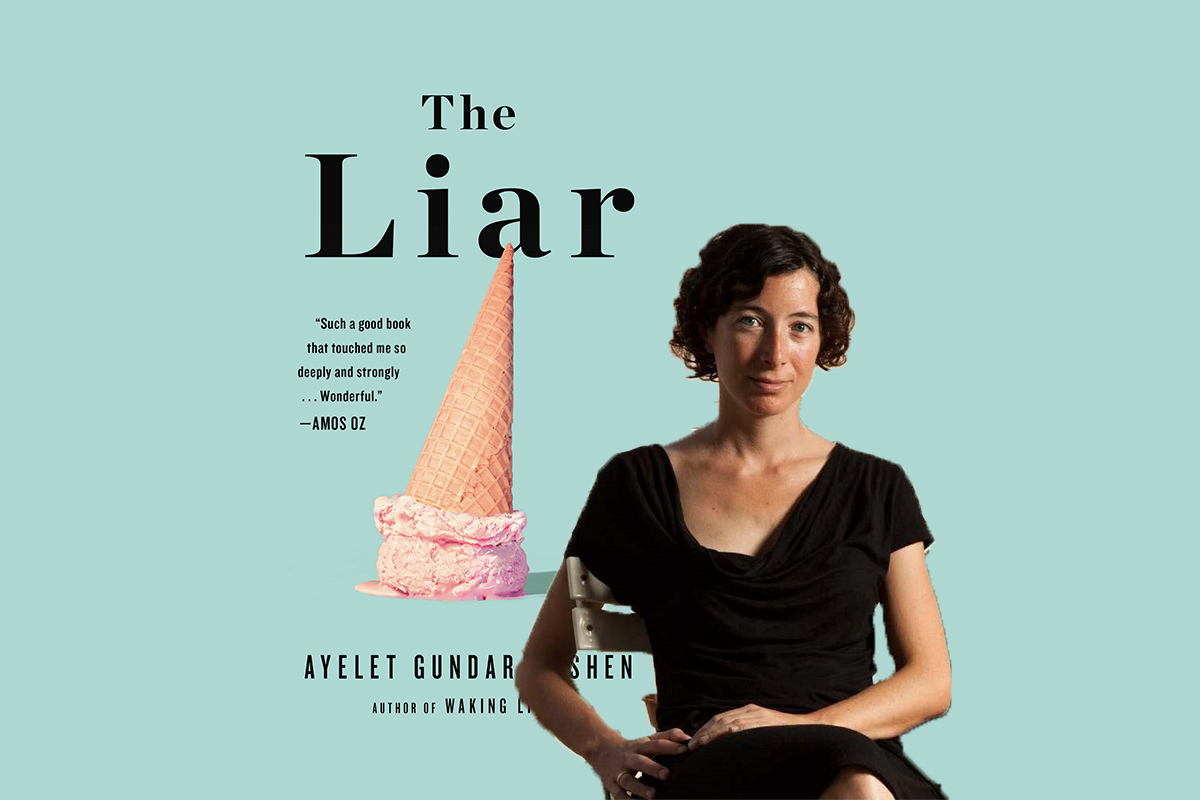

Lies, Imposture, Stupidity (Review Essay) (2021)

Thierry Lenain

Negotiating Authenticity: The Case of “Jesse James’s” Revolver (2021)

Roland Breeur

The Last Judgement (2021)

Massimiliano Simons