Orson Welles had difficulty obtaining funding for his movies, so he raised his own money through acting.

He even did commercial advertisements.

Yet, we can hear in his infamous “frozen peas” outtakes that this was not always his favorite form of acting.

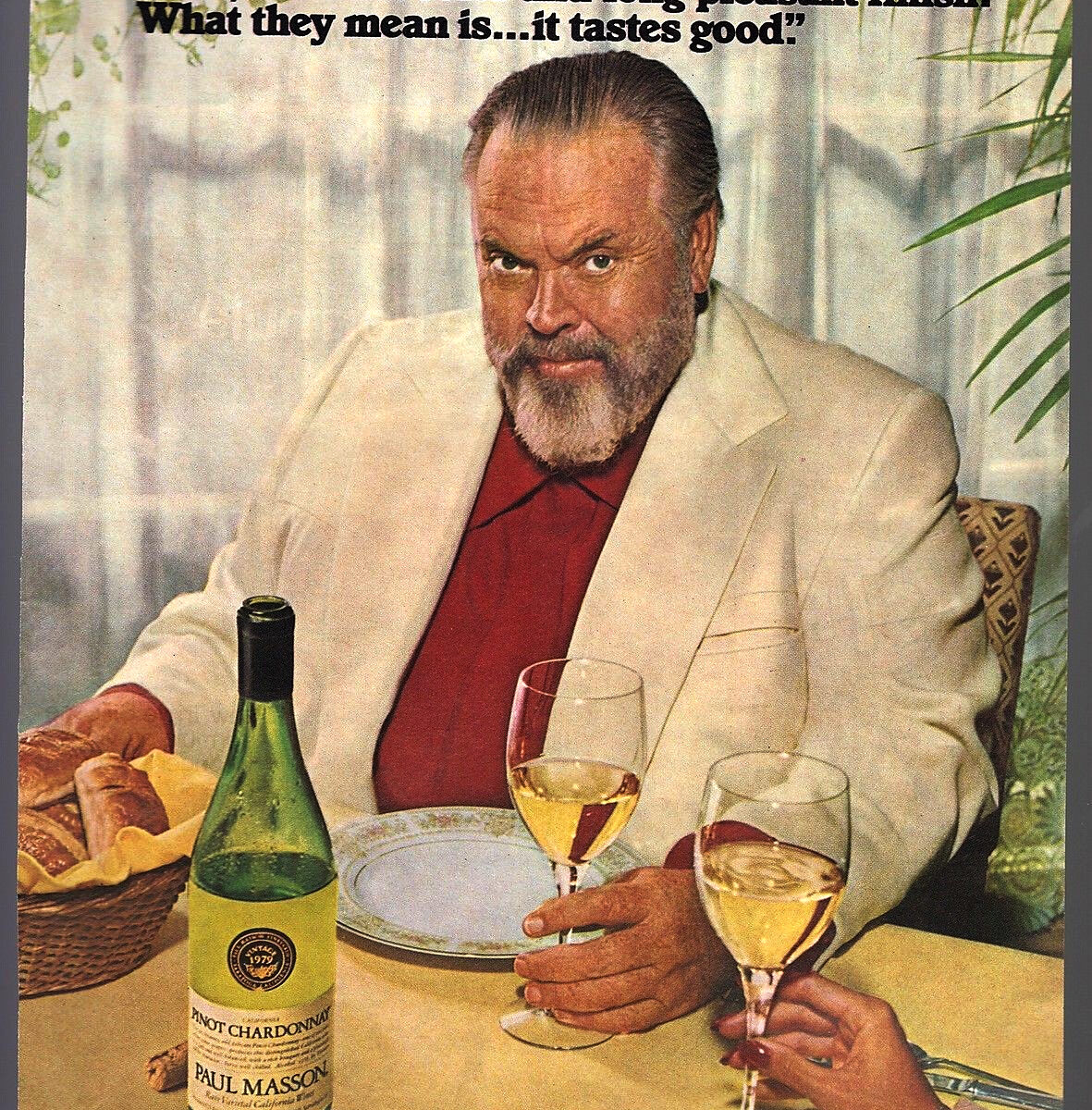

Later, he endorsed Paul Masson wine in television commercials. We will see in the outtakes that he reads from a script. So, he is acting. And yet, the character he portrays is still he himself, still Orson Welles. And his job is to represent the product. If we drink enough Paul Masson champagne, we become drunk. In these outtakes, is Orson Welles intoxicated? Or is he perhaps faking or acting drunk?

The final version uses the footage but with overdubbed audio. Does it feel like a more authentic presentation of Paul Masson wine? We compare the two and wonder, who’s the real Paul Masson?

Both versions were scripted for Welles; both are false self-portrayals in a sense. But, did we feel that the first one was more real or had more power of authenticity of some sort?

And, what about the humor in this parody? Does it not seem like an honest, and yet original, presentation?

These clips serve to introduce our main theme of the originating power of the false, in its relation to fakery. We will combine Deleuze’s writings on determinability in the third synthesis of time with his explanation of Orson Welles’ notion of fakery. Somehow, fakery as forgery or as role-acting can be productive of our authentic self-becoming, and it is based on the temporal immediacy of the now and the next. Self-falsification might be how we continuously vary from ourselves, and it could rest upon a paradoxical structure of time.

Let us begin first by noting that Orson Welles considered himself to be a magician.

He explains:

Fortune telling as stage magic is also fakery for Welles. Yet, this falsification can magically transform the performer into someone too close to the real.

The fakery became real through the acting. Forgery can somehow be authenticity. Welles’ film F for Fake (1973) is partly a documentary on real life painting-forger Elmyr de Hory.

So, we normally think of the forgery as coming after the model it falsifies. Yet, there is a way for self-creative originality to be produced through forged falsification. Consider Welles’ infamous War of the Worlds radio broadcast. It had every appearance of a normal music radio show that is periodically interrupted by progressively unsettling news-flashes detailing an alien invasion. Millions of listeners panicked, thinking that the invasion was real.

Now, notice how Welles confesses he uses normal broadcasting conventions. Then also note that the second reporter thought Welles’ faked broadcast seemed more real than normal ones.

Yet, the broadcast’s believability is not its production of reality. There have since been re-creative variations of it but with different narrative content. Although it began as a forgery, as a fake news story, it nonetheless became a real dramatic form inspiring other variations and tributes. Regarding Welles’ fakery, Deleuze writes:

“the forger cannot be reduced to a simple copier, nor to a liar, because what is false is not simply a copy, but already the model. […] the artist, even Vermeer, even Picasso, is a forger, since he makes a model with appearances, even if the next artist gives the model back to appearances in order to make a new model.” [1]

Now, fakery as the creation of reality has the temporality of becoming. Deleuze writes:

“it is so difficult to define ‘the’ forger, because we do not take into account his multiplicity, his ubiquity, and because we are content to refer to a historical and ultimately chronological time. But everything is changed in the perspective of time as becoming.” [2]

To illustrate the ‘pure event’ of becoming, Deleuze recalls the scenes in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland when her body rapidly expands. As she becomes larger, she of course becomes larger than the size she just was. But in that same stroke, she is also ‘becoming smaller’ than the sizes she is now growing into. If we are assuming she will continue her growth, then in the next moment, she will be larger; but, that coming largerness is still smaller than the even larger size that comes after that. So, it is not that Alice is larger and smaller than herself. Rather, Alice is becoming larger and smaller than herself.

“Certainly, she is not bigger and smaller at the same time. She is larger now; she was smaller before. But it is at the same moment that one becomes larger than one was and smaller than one becomes. This is the simultaneity of a becoming […]. becoming does not tolerate the separation or the distinction of before and after, or of past and future.” [3]

Deleuze’s third synthesis of time is the synthesis of the future: it synthesizes the now with the next, and he roots his account in Kant’s critical analysis of Descartes’ cogito argument, I think, therefore I am. We will put aside many of its complexities to focus on the concept of determinability, which is something like the infinitely tight crack that temporally differentiates the now from the next while at the same time bringing them together into absolute immediacy.

To illustrate self-consciousness as a disjunctive synthesis with our now and our next, Deleuze turns to the story of Actaeon’s transformation. After he happened upon goddess Diana bathing naked in the wood, she turned him into a deer. He becomes aware of this when seeing his new animal form reflected in the water. Actaeon both recognizes it is he himself – for, it is his self staring back at him – while at the same time, he must recognize himself as becoming something completely different than whom he had been right up until then. In a manner of speaking, to be self-conscious means we must look in the water and see a deer, and yet still identify with that other, as if to say, “that is me, but who am I?” Being a self means being an other to oneself, on account of our constant variation over time. Consider, for instance, our first time jumping into deep water. At the moment of the leap, we in a way have determined ourselves as being a capable swimmer. However, we have not yet reached the water and actualized our new status. In that passage between states, we affirm our determinability, our always being glued to the other self we are becoming.

Consider, then, Deleuze’s discussion of the relay characters in Welles’ Mr. Arkardin (1955). Because of how each character follows the other in succession, with every one of them being quite odd but each in their own way, they seem to present a series of metamorphoses, as if one character hands off the baton to the next in a relay race.

Do we not undergo metamorphoses throughout our lives, as if we as well hand off the baton from one state of ourselves to the following different one? Each runner is different, but all are connected by a chain of direct contacts. We see this sort of determinability in Rosenberg’s Cool Hand Luke (1967). When Luke claims he can eat 50 eggs, he is not then really such a person, because no one has done it before. Yet, by making the declaration, he glues himself to his forthcoming self-variation, and in that way affirms his determinability.

Is this something like acting or like making oneself a forgery? Consider this clip of Welles passing himself off as Churchill, who was passing himself off as Welles, who was passing himself off as Othello.

Acting as someone we are not can in many cases be a source of vitality and growth, and an inherent part of every moment of our lives. Perhaps we have some control over our self-forgeries, and we may guide ourselves toward worthwhile and vital selves to become.

Let us end with a celebrity roast. Welles, like all other participants of these shows, makes light of the celebrities with slightly insulting jabs. But not so for Jimmy Stewart. Welles instead roasts some other actors lacking Stewart’s courage to give anti-violent male portrayals. When we emulate admirable traits even to the degree of mimicry, would this necessarily be inauthenticity? Or is there another standard at work? Could not self-forgeries be evaluated according to the vitality, originality, and constructive self-creativity they produce?

[1] Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (London: Continuum, 2005), 141.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Gilles Deleuze, The Logic of Sense, trans. Mark Lester and Charles Stivale (London: Continuum, 2004), 3.